Mali and Burkina Faso recently announced a defiant move imposing bans on US citizens entering their territories in response to restrictions imposed by the US on their citizens. The moves, which took effect immediately, follow reports of similar action by neighbouring Niger via state media.

These West African states, all under military rule, cite the principle of reciprocity after the US expanded its travel ban to include their citizens from 1 January. The decisions are indications of growing tensions between the Sahel region and the US, following a broader push for African sovereignty.

The US restrictions, announced by the White House on 16 December 2025, add Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and several other countries to a list of 39 countries facing full or partial visa suspensions. U.S. president, Donald Trump, justified the expansion on national security grounds, referring to deficiencies in screening, vetting, and information-sharing in the affected countries.

Factors cited by U.S. authorities included visa overstay rates and regional terrorist activity, though absolute overstay numbers from these low-volume countries remain modest and no incidents in the US have involved their nationals.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Fiscal Year 2024 data indicates overstay rates for B-1/B-2 visas ranging from around 5% for Mali to 9% for Burkina Faso, with higher figures for student/exchange categories in some cases, above the global average of 1.15% but based on small admission volumes, contributing only a tiny fraction to total US overstays.

The Sahel region saw significant jihadist violence in 2024, accounting for 51% of global terrorism deaths, according to the Global Terrorism Index 2025, displacing millions locally. However, these threats have remained confined to the region, with no recorded attacks on US soil by nationals from these countries, highlighting the precautionary aspect of the measures.

For Mali and Burkina Faso, this means a complete halt to most immigrant and non-immigrant visas for their nationals, with limited exceptions for diplomats and athletes. The White House described the measures as necessary to protect US public safety, amidst ongoing concerns over terrorism and visa overstays.

Niger was reported to have responded on 25 December 2025, imposing a halt to US visas and entry. It framed it as a defence of dignity and equality. Mali and Burkina Faso followed on 31 December. Mali’s foreign ministry expressed regret over Washington’s unilateral decision, rejecting the security rationale as unjustified by “actual developments on the ground” and lacking prior consultation.

Burkina Faso’s Foreign Minister, Karamoko Jean-Marie Traoré, emphasised reciprocity while reaffirming commitment to mutual respect and sovereign equality. Traoré has challenged stereotypes about migration in regional forums, rejecting the notion that Africans primarily aspire to emigrate to the West.

These bans are rooted in a context of pan-Africanist defiance, as the three states assert independence from Western influence. The Alliance of Sahel States (AES), to which they belong, was established in 2024 to tackle jihadist insurgencies linked to al-Qaeda and ISIL, which have displaced millions across the region, while promoting trade and self-reliance.

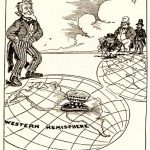

Military coups in recent years have led to the expulsion of French and US forces, with the juntas shifting towards Russia for security support. The bans symbolise a rejection of unequal power dynamics, where African countries are often treated as security risks without reciprocal scrutiny.

The implications are multifaceted. Diplomatically, the moves escalate tensions, potentially disrupting US-Africa relations already strained by Trump’s policies, including the lapse of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) in September 2025, which supported millions of jobs through duty-free trade.

Economically, US businesses face hurdles. Burkina Faso hosts several American gold mines, and the ban could hinder operations and investment. Humanitarian efforts may suffer, with aid workers restricted from visiting the Sahel.

Respected commentators view the bans as an assertion of African agency. Analysts note that while nearly half of African citizens face US visa curbs, only three countries, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, have responded reciprocally, signalling defiance without burning bridges entirely.

Experts on African politics view it as an “assertion of sovereignty in an era of unequal global relations,” highlighting the Sahel’s pushback against Western dominance. Analysts, including former US diplomats, warn that such measures risk isolating the US further, as African states bet on multipolar alliances.

Traoré’s remarks on sovereignty and dignity have resonated widely among pan-Africanists. The bans may inspire others, testing the limits of US influence. What is clear is a growing demand for equitable international partnerships, free from paternalism.