By Lindsay Barrett

Deliberations about global conflicts at the United Nations General Assembly in the last decade or more have been replete with issues that must have inflamed the anxiety level of African diplomatic experts as they contemplate the opinions and decisions of the so-called leaders of world affairs.

The emergence of the ultimate representative of American capitalism, Donald J. Trump, as the highly vocal leader of the Western bloc of member nations, especially after he openly denigrated African nations during his first term by using a dirty curse word to describe them, might also have provoked a mood of pessimistic disenchantment among a substantial proportion of the African diplomatic community.

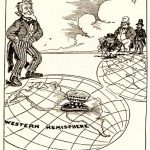

As a consequence, Africa’s perception of global affairs arising from activities leading to hostile actions that unsettle international relations have taken on peculiarly anti-Western attributes and values. As a result, many representatives of African nations have attempted to remain determinedly neutral in their opinions about issues like the Russia vs Ukraine conflict.

Meanwhile most African nations, with the exception of South Africa, struggle to appear as pro humanitarian as they boldly express opinions about the Israeli-Gaza conflict. South Africa’s brave and unique decision to accuse Israel of genocide in Gaza at the ICJ has not been adopted as the universal diplomatic convention of African nations and the reluctance of the majority to do so is thus regarded as a hallmark of the continental assessment of that conflict.

In the meantime, the outburst of one of the most devastating conflicts anywhere in the world in Sudan has focused the world’s attention on Africa’s inability to manage internal crises of stability and major conflict.

Diplomatic responses to globally consequential conflicts emanating from African debates are dependent on the circumstances of economic and political realities that exist in the continent. For example, it has been revealed that East African nations like Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda have maintained a fulsome tradition of importing cereals from Ukraine and are thus likely to sympathise with that country’s determined decision to defend its sovereignty.

Most West African nations, and the republic of South Africa, on the other hand, regard Ukraine as a location for advanced educational assistance and as an extension of the former Soviet Union. They are therefore likely to regard the conflict as an understandable result of Russian disenchantment. But at the same time most African diplomats continue to pay lip service to the principles of anti-colonialism and so regardless of their regional biases they oppose the fundamental act of territorial invasions.

The average African diplomat will therefore prefer to advocate the reversal of the Russian initiative in Ukraine rather than its success. By the same interpretative standard, the average African diplomatic opinion supports Palestinian self-determination and statehood while also supporting Israel’s right to exist.

When considering the outbreak of the conflict in the Sudan, most African diplomats lay the blame on external influences coming mainly from the Middle East but the fact is that the genuine causes of the conflict are locally situated. A point that must be considered is that the rivalries that have become so toxic in the Sudan have their origins in the influence of the military institution having been politicised to an extraordinary extent.

This institutional aberration is dangerously present in several nations in other parts of the continent and so it is an important issue that most diplomatic officials in Africa hope will not assume the Sudanese consequence elsewhere in the continent.

African diplomatic observation of global conflicts provides the basis for discourse on relationships between independent former colonies and ex-colonial usurpers of their cultural values and historical origins. It used to be presumed that major nations like Nigeria and Ghana would always take the lead on interpreting their approach to global conflicts from their former coloniser Great Britain, or that nations like Cote d’Ivoire and Senegal would automatically parrot French attitudes on world affairs.

In recent years this has not been the case, although many observers complain that instead of taking directives from their former colonisers many African nations’ diplomatic representatives seem to be indecisive and reluctant to articulate original positions.

However, this apparent indecision is often based upon a reluctance to be drawn into a position of diplomatic side-taking in global conflicts and this reluctance has become an important element of Africa’s contemporary post-colonial diplomacy. As a consequence, with the exception of South Africa’s major interventions at the ICJ, African involvement in discussions about conflicts on the global scene nowadays often appear as if they are afterthoughts rather than meaningful and relevant interventions.

This might be a misleading impression as it is important to realise that Africa’s interpretation of global affairs is best expressed through the prism of national circumstances and values which are usually not easy for outsiders to understand. As a result, African perceptions and consequences that arise from global conflicts must be regarded by the average observer with careful consideration and caution.