By Editorial Board

The United States’ abduction of Venezuela’s elected president, Nicolás Maduro, sends worrying signals to constituted authority across the globe, no less so for West Africa, a region where external forces have imposed political and economic dominance over its leadership for too long.

Trump’s move was clearly a strategic mistake because it undermined the US’s reputation as a responsible actor in the system of international relations. If it is allowed to stand, then “changing the status quo by force” will be legitimised anywhere in the world. This is not merely a problem for Venezuela. The very foundations of the global order is under threat by this act.

The Trump administration’s action shows impudence and raises serious questions about international law and sovereignty. Its design and implementation are a key part of a troubling pattern of assertive U.S. foreign policy that directly threaten the sovereignty and stability of West Africa. It also reveals a clear and dangerous doctrine of hegemonic interventionism that West African states must urgently recognise and collectively guard against.

The core of this threat lies in the use of extra-legal measures for regime change. The operation against Maduro, involving U.S. special forces and airstrikes to extract a sitting head of state, demonstrated a blatant disregard for international law and the sovereignty of a state rich in resources.

Trump’s action exposes a dangerous new resource for West Africa, a region with a history of coups d’état often incited by external interests,. It suggests that, for a power like the United States, when diplomatic and economic pressure fails, direct kinetic measures may be employed.

This fact has always been known about the US in its power projection but there are growing concerns that its brash approach could embolden similar interventions in West Africa, where political instability might be exploited by external actors to install pliant regimes favourable to their strategic or resource interests, bypassing regional and international legal frameworks.

The flagrant disregard for sovereignty is amplified by expansive justifications for intervention. The Trump administration’s rationale for its Venezuela policy, citing narco-terrorism charges, humanitarian concerns, and democracy promotion, established a precedent of broad justifications.

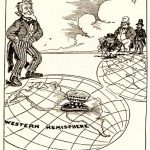

The United States cites the Monroe Doctrine to justify its role in Venezuela, a principle based on regional dominance. The pertinent worry this logic raises is that some great power may claim Africa, and West Africa in particular, as its sphere of influence and that nay determine the extent to which that power feels entitled to impose its political will on the region.

Thus precedent creates a major challenge for West Africa, where countries like Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger face complex crises that include insurgency and political upheaval. It allows an external power to unilaterally define a crisis and its solution.

What this meas is that a government’s internal policies or its partnerships with rivals of Western powers, such as Russia’s Africa Corp, formerly Wagner Group, could be potentially labelled as threats to “regional stability” worthy of intervention. The Venezuela case illustrates that sovereign decisions on security alliances or resource contracts may be subject to coercive override.

The Venezuela strategy also demonstrates the securitisation and militarisation of political crises. Confronted with a weighty political and economic standoff, the chosen solution was not sustained diplomacy but direct military action. This reinforces a global playbook that prioritises hard power.

This is a problematic model for the Sahel. It encourages viewing deeply rooted socio-political insurgencies as simple military problems to be solved by external force, rather than through patient political efforts led by bodies like ECOWAS. It makes the region more susceptible to becoming a theatre for foreign military actions that often exacerbate local grievances and entrench chaos.

What is even more alarming is that this interventionist logic is already operational in West Africa, demonstrated by the recent U.S. airstrikes in Nigeria’s northern state of Sokoto, on December 25, 2025.

These strikes allegedly targeted Islamic State-linked militants, though no proof of this has yet been shown. The attacks were conducted in coordination with Nigerian authorities, but same authorities have not stated if there were specific targets or even the number of casualties recorded.

The action raises questions about the dynamics of consent, external involvement in national security, and respect for sovereignty in a sovereign ally like Nigeria, one of Africa’s economic powerhouses. It acts as a microcosm of the assumption that U.S. threat assessments and military capabilities can complement or augment a state’s own sovereignty over its territory.

The Sokoto strikes demonstrate that direct U.S. kinetic operations, seen in Venezuela, are now a practical tool in West Africa. It signals to capitals in the region that their internal security operations may involve permeable borders and external military support.

Ultimately, the abduction of Maduro in Venezuela and the airstrikes in Sokoto are connected chapters in the same narrative. They reveal a doctrine that views sovereignty as subject to overriding security imperatives. It also exposes international law as flexible, and military force as a primary tool of policy.

For West Africa, a region striving to assert its agency in a multipolar world and navigate partnerships on a non-aligned basis, this is an existential challenge.

As many analysts agree, the defence against this renewed interventionism requires a recommitment to the inviolability of sovereignty, a cautious approach to externally driven militarised solutions.

Most of all, it requires the strengthening of regional mechanisms like ECOWAS to present a bulwark of collective political resolve. The events in Venezuela and Sokoto serve as clear warnings that West Africa must heed.