Part of “Precolonial West African political entities” series

The historical trajectory of the Asante Empire, from late 17th to early 20th century, demonstrates a strategic example of precolonial political centralisation and economic complexity in West Africa. Its emergence was predicated on the control of a prosperous heartland in contemporary Ghana, whose fertility and immense gold reserves provided the material base for its formidable state structures.

Scholarly analysis of the mid-17th century in West Africa identifies it as a period of significant systemic flux, where the decline of established hierarchies created the conditions of possibility for the Asante Empire’s rise. This fundamental realignment is best understood as a complex causal sequence, emerging from the interplay of three distinct yet interrelated factors.

These were the political decline of dominant states like Adansi, the economic magnetism of gold reserves that integrated the region into nascent Atlantic trade networks, and the decisive agency of leadership, exemplified by Oti Akenten’s founding of Kumasi around 1660. This convergence of conditions facilitated the Asante, as an Akan people, to transform regional instability into a platform for imperial statecraft.

It is believed that the primary objective of his military expeditions was the political consolidation of fragmented groups, an endeavour that successfully engineered the shift from a loose confederation to a centralised hegemonic empire. The succession of Obiri Yeboa after Akenten guaranteed continued political consolidation.

His fatal defeat, however, by the Denkyira tributary of Dormaa, marked a definitive rupture. This setback served as a historical catalyst rather than terminate the political project. It effectively cleared the political landscape, enabling the rise of Osei Tutu, Yeboa’s nephew, whose leadership would ultimately transcend the earlier, more limited model of confederation.

Osei Tutu’s formative years were spent in the Denkyira court, where he was held as a political hostage, a common practice of the Akan. This period constituted a de facto education in Denkyiran military strategy and administrative statecraft. After his departure from Denkyira and subsequent invitation to assume the Asante leadership, his accession as Kwamanhene was marked by the immediate implementation of transformative reforms, the blueprint for which was largely derived from his intimate observation of the Denkyira polity.

The period culminating in 1699 witnessed the efficacy of Osei Tutu’s political strategy, which targeted the very legitimacy of Denkyira’s tributary system. By instituting a policy of integrative citizenship for conquered peoples, he engineered a significant erosion of Denkyira’s client network, thereby securing the mass of allied support necessary for his imperial project.

The Battle of Feyiase in 1701 eventually changed the regional balance of power. The Denkyira possessed a major technological advantage through their alliance with the Dutch, which provided them with firearms and cannons. The Asante strategy, however, demonstrated superior tactical skills. They effectively neutralised Denkyira’s material superiority by successfully cutting their maritime supply lines and blockading their trade routes.

The power of the Denkyira empire ended with the death of its king, Ntim Gyakari. Under Osei Tutu’s successors, Asante dominion grew through the annexation of kingdoms like Twifo, Wassa, and Bonoman by 1715. A major strategic achievement was securing coastal access by 1820, which gave them direct access to trade in gold and ivory with Britain and Holland.

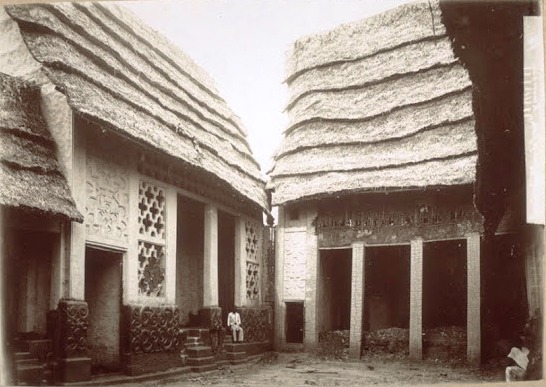

At its peak, the Asante Empire governed three to four million people across hundreds of miles, including parts of present-day Cote d’Ivoire and Togo. Its governance was a sophisticated hierarchy, with the Asantehene at the top, with the Golden Stool as a symbol of his authority, a sacred object believed to embody the nation’s soul. This stool, introduced by the priest Okomfo Anokye, was reserved exclusively for the king, as a reinforcement of his divine authority.

Beneath him, a council of elders, the Asantemanhyiamu, held legislative power and could even destool an unfit ruler. A multi-tiered bureaucracy managed affairs, with ministries for foreign relations and a Gyaasehene overseeing finances, while Anokye’s 77-law code provided a legal framework, with punishments like death or banishment commutable by the king.

Religion played a central role. The Asante venerated Onyame, a supreme deity, alongside lesser gods, mediated by priests, known as Akomfo. A prevalent belief in ancestor worship resulted in the custom of human sacrifice, especially during the funerals of high-status individuals. Those sacrificed were meant to serve the deceased in the afterlife.

Asante society was characterised by a patriarchal political structure and a widespread system of domestic slavery managed by the sikapo elite. However, a strict patrilineal model was balanced by the enduring power of the matrilineal abusua (clan). Within this dual-gendered system, women exercised legally recognised rights that affirmed their social indispensability. These included the initiation of divorce and a primary claim in child guardianship, as children’s lineage and inheritance were traced through them, ensuring their structural importance despite the overarching patriarchal context.

The empire’s prosperity drew European attention, but also conflict. The Anglo-Asante wars, which was fought from 1823 to 1900, tested its might. The first Anglo-Asante war, between 1823 and 1831, began with major Asante victories. In one decisive battle, Asante forces killed British General Charles MacCarthy and retained his skull as a trophy of war. However, the British eventually used their superior technology to gain an advantage in battle. But the borders remained mostly unchanged.

The inconclusive Second Anglo-Asante War between 1863 and 64 maintained a volatile status quo, which escalated a decade later into a definitive third conflict between 1873 and 75. It was triggered by an Asante incursion, and it ended catastrophically for the Asante with General Wolseley’s systematic destruction of Kumasi. The ensuing Treaty of Fomena imposed punitive indemnities and trade terms, but it served merely as a provisional instrument within the broader, and still unresolved, trajectory of British imperial ambition in the region.

Britain imposed a protectorate on the Asante in 1895 and exiled King Prempeh I, motivated by fear of French and German expansion. The final uprising erupted in 1900. Its direct cause was the British representative Frederick Hodgson’s demand to sit on the Golden Stool, an act the Asante considered a deep cultural and spiritual insult. It sparked a revolt led by the queen mother. The Asante mounted a strong resistance, and inflicted heavy losses on the British. They successfully kept the Golden Stool hidden, preserving its sanctity, but the British proceeded with formal annexation on January 1, 1902.

Returning Prempeh I to a ceremonial role required a serious negotiation of power.This compromise guaranteed the preservation of Asante kingship under a republican framework. This legacy of resilience is presently embodied by Asantehene Osei Tutu II, whose reign since 1999 reinforces the Kingdom’s vibrant existence as a protected sub-national polity.

The empire’s sophisticated output in material culture and governance systems continues to provide a serious counterpoint to narratives of African precolonial absence. Once filtered through the colonial-era lens of observers such as Bowdich, Asante achievements are now foundational to deconstructing those very perspectives, affirming the continent’s complex history in global academic discourse.